Experienced Sonic Fictions

By Leandra Lambert

Abstract

The research grew out of experiences with deep listening and a free form of soundwalking in urban and non-urban environments in Rio de Janeiro. The practice consists of intersensory drifts with field recordings, photos, drawings and texts. This process emphasises the relationship between listening, intersensoriality, imagination and memory, the entwinement between what is physically listened and ‘non-cochlear’ sounds and the resonances created by the mix of acoustic spaces and sonic reveries. This experimental methodology led to the construction of experienced fictions, a poetic and non-realistic account of events used to produce art linked to everyday life and fiction.

Keywords: listening, hodology, fictions, intersensoriality, subjectivities, art, process.

An introduction to “Atlântica” and some reflections on soundwalking and sensory transformations

In the year 2000 Brazil went through a series of official celebrations for the 500th anniversary of the country. Such celebrations were not well received by a portion of the population, a reaction that stemmed from its history of colonialism and slavery under the rule of the Portuguese. As a long lasting consequence of this slavery, the largest portion of the black population still belonged to socially disadvantaged strata, many of them living in favelas. These were experiencing an especially violent moment, with intense clashes occurring daily between different groups and the police.

Compared to the years between 1990 and 2000, the 21st century is a more optimistic time for both Brazil and Rio de Janeiro. However, significant social problems remain, such as the enormous rise in the cost of living in Rio de Janeiro and the processes of gentrification emerging around events such as the Olympic Games and the World Cup. This recent optimism has also obscured ongoing social problems, such as low quality public transportation, healthcare, and education, despite extremely high taxes. Homelessness remains a significant problem, with people often removed to less visible areas, forming a legion of ‘invisibles’. These kinds of problems triggered the 2013 riots throughout the country, especially in Rio. This unrest exposes negative aspects beneath the more ‘optimistic’ surface of things.

During this period I began to examine three distinct Atlantic sites: the Atlantic Ocean, the Atlantic Forest, and the Avenida Atlântica (Atlantic Avenue). In 2000, I had not formulated an approach to examining these spaces; instead, I composed music as a response to these sites. It was only in 2009 that I began to perform, in a more systematic way, a series of walks, of peripatetic drifts along Avenida Atlântica, guided by sound stimuli, harvesting not only sounds, but also objects, images, impressions and experiences. Thus emerged the large “Atlântica” series. In this work, I seek to consider the problematic times we live in in Brazil, some of which arise because of our colonial history. I am constantly studying the everyday life, culture and mythology of these Atlantic places and their inhabitants, creating stories from them.

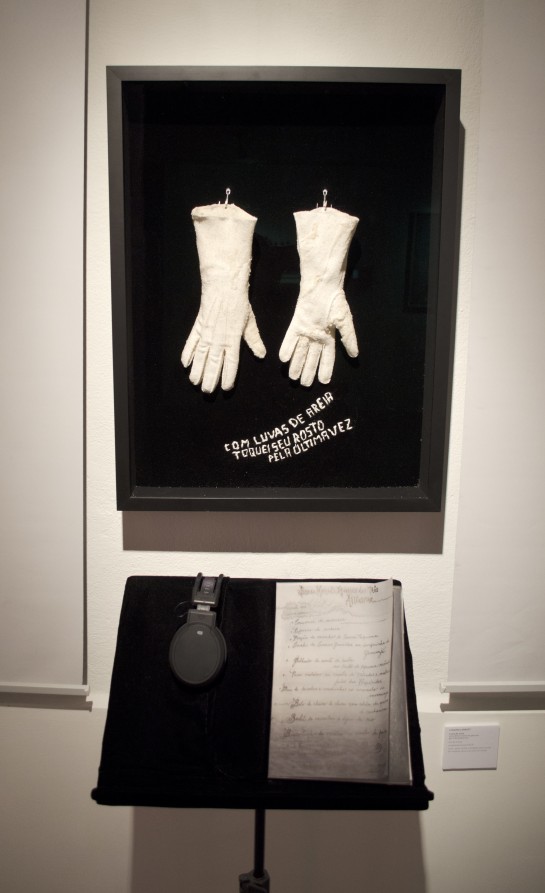

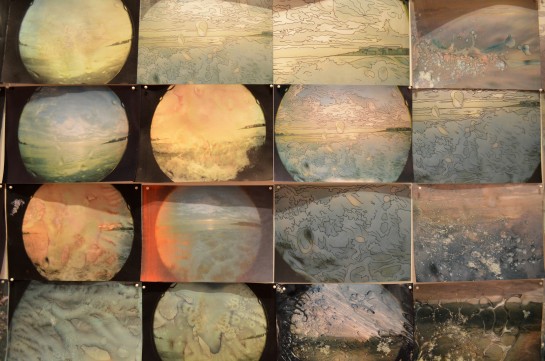

Figure 1 – The morning, when it comes, is never the same – I – Ocean. Part of a work made with 90 photos and drawings, salt and sea water, Leandra Lambert, 2013.

Besides all these geographical, political and historical issues, this journey also began as a poetic investigation into sound and its ability to spread beyond boundaries, to vibrate skins, bodies and atmospheres, to create territories and crossings. This process of walking guided by listening provoked a more accurate attention to the other senses.

In a quest for careful and unconditioned listening, the work was guided by the sounds heard on pathways. The beginning of the process is similar to a soundwalking practice, as proposed by Westerkamp, after Murray Schafer – a walk focused on listening to “rediscover and reactivate our sense of hearing.” (Westerkamp 1974, rep. 2007, p.49). The concept of deep listening, developed by Pauline Oliveros, also played a fundamental role:

…learning to expand the perception of sounds to include the whole space/time continuum of sound – encountering the vastness and complexities as much as possible. Simultaneously one ought to be able to target a sound or sequence of sounds as a focus in the space/time continuum and to perceive the detail or trajectory of the sounds or sequence of sounds. (Oliveros 2005, p.xxiii).

I seek this kind of sensitive observation of the sounds co-produced by the landscape, different environments and their inhabitants. But the routes covered soon led to a multi-sensory experience of place; there was a mix of smells, tastes and tactile sensations, which emerged as images, writings and experiences. The experience of a sonic drift configures itself as the fundamental territory of productive deviations, a terra incognita that is renewed at each experience, rich in possibilities. A sonic drift is realized when one is wandering through space and sound, in a dérive (an unplanned journey) of body and thought. The configuration of the senses is contingent, defined by innumerable conditions and historical, social, cultural, and personal crossings. Sensibilities and subjectivities can approach what configures the ‘common sense’ of an era, of a culture — or deviate from it in different ways, be they more restrictive, selective or expanded, under more or less favourable conditions.

Video 1 – Oceanic Nocturne (Fragment). Video and sound composition, Leandra Lambert, 2012-2013

Theory and practice of a sonic met-hodology

The methodological approach emerged from the experiments and a kind of knowledge that accepts uncertainties and ambiguities. The experiments dealt with the poetic of detours and deviations closely linked to Debord’s dérive: walking through places with a playful and constructive attitude, guided by the solicitations of the land and the encounters that occur in a transformative and deconditioned process (Debord 1956). But there are some fundamental differences: the soundwalks are not restricted to urban areas and, consequently, to the current notion of psychogeography; they always result in some material traces and constructed fictions.

The concept of hodology is also applied to this method of walking. The concept was utilised by Gilles Tiberghien (2012) in his study of aspects of modern and contemporary art, dealing with the personal building of paths or journeys. The term derives from the Greek hodos, meaning route, journey or path (Jackson cited in Tiberghien 2012). John Brinckeroff Jackson notes that the root hodos is also found in methodos: “a way of regular and systematic action” (cited in Tiberghien 2012, p.163). In the particular case of my hodological practice, the method opens itself to chance – to interferences and irregularities – the system escapes the strict rules and seeks, according to Rimbaud, a “derangement of all the senses” (1993, p.16).

The hodological method is consistent with this open and processual approach. Tiberghien observes the dialectical opposition between two kinds of routes. The first kind aggregates pre-existing routes, streets, roads and the surfaces built to facilitate and accelerate access. They are the passages that correspond to habit. The second kind aggregates the routes practiced and invented anew each time. Hodology favours the second kind of route: a wandering path, one that can be dangerous or a kind of walking that is seen as a “waste of time” (2012, pp.163-165).

Tiberghien emphasizes the value of art to the hodological method, arguing, “it enhances the dimension of the sensitive and emotional experience of walking” (Tiberghien 2012, p.164). The act of listening, instead of being passively exercised, has an active force:

…when you listen, you enter in synergy with the world and the senses, a listening/touch that is the essence of what is called visceral reaction — a response that is both physiological and psychological, mind and body.” (Dyson 2009, p.4)

This kind of experience is reflected in the work of Brazilian visual artist Hélio Oiticica, who developed the concept and the practice of the suprasensorial experience (Oiticica 2011b, p. 272). He valued the use of drifts, in Rio de Janeiro, as a fundamental part of his work. About the suprasensorial experience, he said:

It is the attempt to create, by means of increasingly open propositions, creative exercises, dispensing even the object such as it became categorized […]. They are directed to the senses, through them, from “total perception” they lead the individual to a “suprasensation”, to the dilatation of his usual sensorial abilities, to the discover of his inner creative center, of his dormant spontaneity of expression, conditioned to everyday life. […] My own propositions seek to “open” the participant up to himself – there is a process of interior dilation, a diving into oneself that is necessary for that discovery of the creative process… (Oiticica 2011b, pp.236-237-extract from interview 1967)

The total suprasensorial experience can occur in the “ambulatory delirium” (Oiticica 1996; 2011a): the transformation process is deepened by the differentiated experiences over the usual landscape. In his art work Oiticica dislocated situations and spaces with the intention of producing opportunities for people to have bodily, subjective, and sensory experiences with transformative potential. He created living and imaginary maps, to be walked upon, felt and experienced (Oiticica 2011). Resonating with Oiticica’s practices, my own nomadism occurs mostly in my neighbourhood, de-familiarising spaces, suggesting new ways to look, new perceptions and sensations. I seek the difference in what is close to me, and I seek empathy for the other, for the distant. It is possible, in this way, to travel in any place and use disorientation and wandering as a methodological process.

This kind of action is also linked to the way sound transgresses boundaries and blurs the alleged physical and perceptual boundaries of space. There is a grey area that mixes acoustically perceived sounds, and sounds that are remembered or imagined (David Toop 2010). Each one of us hears these sounds with different levels of frequency and intensity; they are an embodied experience rather than an exterior perceived experience. They are infra-sensorial sonorities with which we identify ourselves, sounds from the deep, a voice from the inside that reacts to the exterior and formulates the outside. We are constantly engaged with our auditory imagination, and this transforms our perception of space and things.

Kim Cohen (2010) argues that there are some elements of sonic art that do not depend on physiological hearing. It is a conceptual sound art drawn from attentive listening in its broadest and intersensorial sense. Just as there was once thought to be a ‘non-retinal’ visual art, after Duchamp, one can also think about this ‘non-cochlear sonic art’ (ibid).

Pan-sensorial walking: methodologies of listening

The artistic experiment begins as a non-programmed soundwalk but the condition of being guided by sounds changes during the walk. The attentive listening initiates a process that changes the perception of all the senses. I am guided by different sensory stimuli, being fully aware of each sensorial experience – or their mix – at different moments. After the initial exercise of the soundwalk, there are more visual, tactile, kinesthetic, and synaesthetic moments. This kind of freestyle soundwalking helps to open the senses to a wider experience of the ambient. Thus, listening assumes its broad sense, beyond the strict confines of the auditory. In my practice I listen to the landscape, and to the body, as well as to non-cochlear sounds. Oliveros states, “such expansion means that one is connected to the whole of the environment and beyond” (2005, p.xxiii). These experiences highlight how sound considers the poetics and politics of noise and silence and plays a decisive role in the process of an intersensorial liberation.

All forms of sound present in an environment are perceived by our auditory cortex and constitute our soundscape, whether we are aware of it or not. Increasing our attention to this landscape opens up countless possibilities (Oliveros 2004; 2005). The results of this method may or may not include an audio construction or a musical composition, but the exercise of listening in a drift is crucial to the elaboration of these experimented fictions, regardless of the formal outcome, be it drawings, text, audio or mixed media. The concrete realisation of the methodological process occurred in the middle of 2009. A period of intensive wandering through these landscapes (avenue, ocean, forest) occurred between 2011 and the beginning of 2013. Later, I exhibited elements of this research in a solo exhibition titled “Danças Atlânticas” (Atlantic Dances) at CCJF, Rio de Janeiro.

Soundwalking the Atlantic Avenue

I walked through Atlantic Avenue – Copacabana beach and its surrounds – at many times of the day, on different days of the week, throughout the year. The weather conditions differed both during the course of a day as well as seasonally, affecting my sensorial perceptions. The sounds and sensory stimuli of an overcast Monday morning in winter were different from those of a sunny Sunday afternoon or a hot Friday night just before New Year’s Eve. So too, the voices of many cultures could be heard at this time of year as people came from around the world to celebrate New Year’s Eve along the Avenida Atlântica.

At many times, I took small walks through different spaces of the Avenue, walking along the beach, around the public bars, stopping to listen to fragments of conversations, trying to imagine how they started and how they might end. I would camouflage the recorder inside a backpack so as to discreetly document these sounds. This was necessary in order to maintain the appearance of someone just walking the space, a kind of nonparticipant observation. I initiated some test recordings at the beginning stages of these artistic experiments. Several of the early field recordings contain noise and distortion, and many sounds cannot be clearly heard. Technical flaws are part of the process and if some microphone noise enters the recordings of a casual conversation between lovers, amongst traffic, children playing and the ocean waves, I accept that this is part of the process of using technology. It then becomes part of the work; these artefacts of sound are as important as the sounds heard during the soundwalks. There are no precise notes about the process, but there are lots of scribbles and sketches about the experience, photographs and drawings with salt water, and other traces of the walk. Chance, chaos, error and noise are part of the work.

I walked many times from one end of the beach to the other. At either end were two military bases, one at Leme (Forte Duque de Caxias) and another one at Posto 6 (Forte de Copacabana). Inside the Leme base, there is a forest reserve – a bit of Atlantic Forest that once covered all the territory of Rio de Janeiro from the mountains to the beach. The Atlantic Forest is located along the length of the Atlantic coast-land of Brazil, and is one of the richest environments on the planet. The avenue shelters an Atlantic microcosm, a partially hidden zone of forest at Leme, situated in front of the Atlantic Ocean. This is an ocean of ‘ressacas’, extreme breakers and undertows, loud, booming and sometimes dangerous sounds.

During the walks the history of the various sites became more and more present in the process. Sometimes I wandered all day long, even after the batteries in the audio recorder died, taking pictures with different cameras and imagining what could have happened in the time between the chaotic and lively environment that we see today and the idyllic images of this area taken in the 1920s depicting beautiful houses and people dressed in glamorous clothes. At other times I imagined the sounds of places that appear in rare drawings and paintings from the last years of the 19th century – when Copacabana was a wild environment – to fifty years later, when the almost unbroken row of high buildings that cross the skyline were built.

Instead of recording the soundscape, I simply walked and listened with lively attentiveness. After these undocumented soundwalks, I began to seek other means of constructing testimonies of my listening experiences. This resulted in the composition of small objects – stones and debris – resulting in concrete or fictitious collections, images and narratives. The constructed relations between a specific route, and the exercise of listening are also matters for the construction of experienced fictions.

During and after the walks the fictions began to take shape, from recent sensitive experiences in constant feedback with the imagination and the memory. This kind of narrative — be it recorded, written, spoken, drawn or ritualized — is part of the construction of experienced fictions, or ‘fabulations’. The concept of fabulation is presented in the writing of Gilles Deleuze, after Bergson (Deleuze, 1990). The fabulation, unlike the classical fiction, is not intended to be true or even credible; it is performed without disguising its quality of invention and non-realism. No sort of power of truth is intended; there is no moral in fabulation. Instead the function of fabulation “…gives the ‘fake’ the potentiality that makes this ‘fake’ a memory, a legend, a monster” (op.cit, p.183). There is always a crossing between real and fiction, the overlapping of times, metamorphosis and transformations in subjectivity. These processes can be integrated into and become part of a methodology.

The construction of experienced fictions – some artworks, paths and openings

Figure 2 – About time and the city – I. Objects and text, Leandra Lambert, 2011. From left to right, from back to front: 1. Smoke from the rush hour of Friday; 2. Wet sand from this morning; 3. Sound of the last New Year’s Day fireworks; 4. Air of melancholy from a cloudy afternoon; 5. Blow of a carnival drum; 6. Effluvia of hot asphalt in January; 7. Sea spray in a summer dawn; 8. Perfume of night girls passing by; 9. Undertow at the nocturnal sea; 10. Seawater after too much sun; 11. Crystal of a finger in the water; 12. Cap for an oblivion; 13. Egg of little mermaid; 14. The last gasp of a fish; 15. Block of ocean

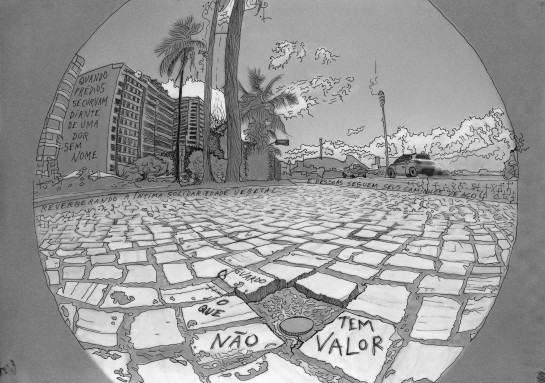

Figure 3 – The street from the inside – What has no value. Drawing of a triptych which also includes a photo and a written Portuguese stone from the pavement of the promenade at Atlantic avenue, Leandra Lambert, 2013

Practicing the hodological method, I built experienced fictions. These take multiple forms. One of these forms is intersensorial cartographies: mappings that are not restricted to vision and language and that also seek to highlight the infra- and supra-sensorial dimensions of a soundwalk.

The initial material consisted of a series of cartographic-poetic explorations derived from the walks. Most of these works mix sound, text, textures and visual elements. They compose a series of atlases to get lost in, of real and imaginary reports, of reinvented myths, histories and stories.1. What emerged from the construction of atlases and cartographies were a series of lists, letters and charts, titled ‘Charts from fathomless lands’, in which I write as someone from another time – but someone still lost in the same Atlantic space I was wandering, someone inhabiting forgotten and unseen cracks and corners.

Figure 4 – Ironic-oneiric map – I. Digital collage, Leandra Lambert, 2010.

In one of my first cartographic works, “Pequeno Atlas Imaginário das Três Atlânticas” (Small imaginary atlas of the three Atlantics, 2011), I explore several mythologies, stories, concepts and experiences, centred on the Atlas and the Atlantics. The work is composed of a book, an Atlas from 1983, which incorporates visual-tactile-olfactory interventions, including a sound piece built into the book that is listened to via headphones. The sounds consist of a ponto (a religious afro-Brazilian chant), dedicated to Iemanjá (the goddess of the seashore). It is mixed with ambient soundscapes recorded at Avenida Atlântica. These recordings were made at several locations: at the sands of the beach, at the Copacabana promenade near the sea, and on different occasions, for example, Carnival and the World Cup. These sounds and experiences were part of my recordings and art works. Though most sounds were concrete recordings, made during the walks, some sounds were synthesized. I also used found samples, creating overlaps and mixings, without purisms. Finally, my own voice joined this sound montage, in a poetic fiction built from my research and my Atlantic experiences and memories. I adopted a method of editing and using collages that was similar to those I visually applied to the “Ironic-oneiric map I” and during the creation of the first visual atlas. In some more recent works, like the series “Charts from fathomless lands”, this concept of atlas is present in more subtle ways, from the books, letters and charts to the sound compositions.

Audio 1 – Small imaginary atlas of the three Atlantics. Sound composition of the work that also includes a visual/tactile/olfactory atlas, Leandra Lambert, 2011

By using the atlas structure, a fundamental reference is made to Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas (an extensive work that began in 1927 and was left unfinished by 1929, the year of Warburg’s death). When working on his compilation of images in the form of a gigantic atlas, Warburg had the intention to transform the social body. Memory played a significant role to Warburg (2009). He understood that images were powerful reservoirs of the collective memory of a culture; in seeking to grasp their meaning he was also searching for deep debates, the possibility of curative effects, healing rifts in the social body and therapeutic transformations in the spirit of the age (Agamben 2009). As Giorgio Agamben notes, Warburg sought to build “fantasies for really adult people” (2009). In the context of a given culture, the use of the atlas form does not happen as a purely formal resource. Didi-Huberman (2010) adds that the choice of constructing an atlas implies the pursuit of an unusual, transverse kind of knowledge of our world. This process takes place when one puts things outside their normal classifications. From these affinities a new kind of knowledge can be glimpsed that opens our eyes (and ears) to certain aspects of our world and our perception. Such observations may apply not only to the construction of a visual atlas, but also to sonic and inter-sensory texts. Creating an atlas produces the desire to decompose and recompose stories, times, spaces, and worlds – transformation permeates all of this terra incognita. The cartographies, mappings, charts, sober or chaotic compositions of the many atlases already assembled, contain a restlessness that is also present in movements into the unknown, the travels, wanderings, drifts, diasporas, detours and deviations. The dynamics of these two forms of unrest oppose and complement each other without ever solving the ancestral conflict between the sedentary and the nomadic; house and street; the silent and sheltered library and the adventurous ship in the turbulence of oceans; textual experiments and sensory perception; rooting and flight; finding a safe haven and getting lost in the world.

Figure 5 – The morning, when it comes, is never the same – I – Ocean. Detail, polyptych made with 90 drawings and photos. Leandra Lambert, 2013.

Conclusion

I believe that anything involving sound is porous, shifting and ambiguous. Sound is an irreducible compound, a mixture of feeling and imagination. Sounds can be produced and edited using poetic, scientific, and technological resources, but always referring to a beyond/through the sound. The sonic phenomenon presupposes mixing, contamination, and a degree of uncertainty and impurity. Sonorities cross us with tactile and kinaesthetic sensations, subtle or intense, with visual images evoked by the individual repertoire, textual fragments, impressions, contaminations, and many kinds of reminiscences. Sound is never pure; I recognise the impurity of sound as fundamental. The perceptual focus on sound makes all the other senses become more porous, unfocused, mixed and open to the multiplicities of outer space and the presence of others.

The practice of walking down the streets with no apparent aim is culturally closer to the notion of vagrancy than the notion of work, creativity and productivity. I question this concept in my practice. Strolls can be works of sensory transformation. I create situations for ambiguity and ambivalence about notions of vagrancy/productivity. I seek to produce art from wandering, to construct fictions from my experiences in these Atlantic strolls, starting with the relationship between listening and peripatetic geographies.

Practicing the methodology of hodological incursions and sensory rearrangements to construct fictions enhanced my art practice. Different forms of materialising experiences and imaginations are now mixed in inextricable paths. The immersion in the landscape, accepting all chaos and complexities of the environment, also changes the way I hear, see and feel my own city and its vicinities. This method allowed me to constantly renew my relationship to a space, it also intensified my perception of a place I have lived in for most of my life.

Figure 6 – The day, when it ends, is never the same – I – Avenue. Detail, polyptych made with 40 drawings and photos. Leandra Lambert, 2013.

Footnotes

- The origins of the name “Atlantic” derives from Atlas, the mountain chain in northwest Africa that oversees the passage from the Mediterranean Sea to the Atlantic Ocean, named after the rebel Titan who, in Greek mythology, was punished with the burden of carrying the celestial sphere over his shoulders. [↩]

References

Attali, J., 2004. Noise and Politics. In: ed. Cox, C.; Warner, D. Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music. New York: Continuum.

Augé, M., 1997. Não-Lugares: Introdução a uma Antropologia da Supermodernidade. Campinas: Papirus.

Augoyard, J; Torgue, H. (ed.)., 2008. Sonic Experience: A Guide for Everyday Sounds. Montreal: McGill-Queen`s University Press.

Benjamin, W., 2006. Passagens. São Paulo/Belo Horizonte, Imprensa Oficial do Estado/Ed.UFMG.

Brett, Guy., 2005. Brasil Experimental - Arte/Vida: Proposições e Paradoxos. Rio de Janeiro: Contracapa.

Bull, M; Back, L. ed., 2003.The Auditory Culture Reader. Oxford/New York: Berg.

Caesar, R., 2008. O Tímpano é Uma Tela! In: Arte e Música. Rio de Janeiro: Metrópolis Produções Culturais & Caixa Cultural.

Cage, J., 1973. Silence: Lectures and Writings by John Cage. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

Cardiff, J., 2005. Interview with Kelly Gordon. Avaible from: http://hirshhorn.si.edu/exhibitions/description.asp?Type=past&ID=20.

Cauquelin, A., 2007. A Invenção da Paisagem. São Paulo: Martins Fontes.

Certeau, M., 2008. A Invenção do Cotidiano: Artes de Fazer. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes.

Cox, C; Warner, D. ed., 2004. Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music. New York: Continuum.

Criton, P., 2012. O Ouvido Ubíquo: Escutar de Outro Modo. (The Ubiquitous Ear: Other Ways of Listening). Conference presented at USP São Paulo, September 6, 2011. Portuguese version by Silvio Ferraz published in: Cadernos de Subjetividade, PUC-SP, São Paulo, year 9, number 14, pp.53-61.

Debord, G., 1956. Methods of Détournement - Published in Les Lèvres Nues #8. Available from: http://library.nothingness.org/articles/SI/en/display/3.

Debord, G., 1958. Theory of the Dérive. Published in Internationale Situationniste #2, 1958. Available from: http://library.nothingness.org/articles/SI/en/display/314.

Deleuze, G., 1990. Imagem-Tempo. São Paulo: Brasiliense.

Deleuze, G., 1992. Conversações. São Paulo: Editora 34.

Deleuze, G., 1997. Crítica e Clínica. São Paulo: Editora 34.

Deleuze, G., 1998. Diálogos. São Paulo: Escuta.

Deleuze, G.; Guattari, F., 1996. Mil Platôs: Capitalismo e Esquizofrenia. Vol.3. São Paulo: Editora 34.

Deleuze, G.; Guattari, F. 1997a. Mil Platôs: Capitalismo e Esquizofrenia, Vol. 4. São Paulo: Editora 34.

Deleuze, G.; Guattari, F., 1997b. O que é a Filosofia?. São Paulo: Editora 34.

Didi-Huberman, G., 2003. O Anacronismo Fabrica a História: Sobre a Inatualidade de Carl Einstein. In: Zielinsky, M., ed. Fronteiras: Arte, Crítica e Outros Ensaios. Rio Grande do Sul: Ed. UFRGS.

Didi-Huberman, G., 2010. ATLAS: How to carry the world on one’s back? Madrid: Museu Reina Sofia.

Dyson, F., 2009. Sounding New Media: Immersion and Embodiment in the Arts and Culture. Berkeley: UC Press.

Flusser, V., 1996. Texto/Imagem Enquanto Dinâmica do Ocidente. in Cadernos RioArte, ano II, n.5.

Foster, H., 1996. The Return of The Real. Cambridge/London: MIT.

Gibson, J.J., 1986. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. New York: Taylor & Francis Group.

Guattari, F., 1990. As Três Ecologias. Campinas: Papirus.

Howes, D. ed., 2005. Empire of The Senses: The Sensual Culture Reader. Oxford/New York: Berg.

Ihde, Don., 2003. Auditory Imagination. In: Bull, M.; Back, L. ed., The Auditory Culture Reader. Oxford/New York: Berg.

Jackson, J.B., 1984. Discovering The Vernacular Landscape. New Haven/London: Yale University Press.

Jackson, J.B., 1994. A Sense of Place, A Sense of Time. New Haven/London: Yale University Press.

Kahn, D., 1990. Acoustic Sculpture, Deboned Voices. Available from: www.douglaskahn.com.

Kahn, D., 1999. Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Sounds In The Arts. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Kahn, D., 2002. Digits on the historical pulse: Being a way to think about how so much is happening and has happened in sound in the arts. Available from: www.douglaskahn.com.

Kahn, D., 2005. The P0litics of S0und / The Culture 0f Exchange. Available from: www.douglaskahn.com.

Kaprow, A., 2003. Letter to Mason Gross, 28/05/1959. In: Hendricks, G. ed. Critical Mass: Happenings, Fluxus, Performance, Intermedia and Rutgers University 1958-1972. New Brunswick: Rutgers.

Kelly, C. ed., 2011. Sound - Documents of Contemporary Art. London/Cambridge: Whitechapel/MIT.

Kim-Cohen, S., 2010. In the Blink of an Ear: Toward a Non-Cochlear Sonic Art. New York: Continuum.

Kwon, M., 2004. One Place After Another: Site Specific Art and Locational Identity. Cambridge: MIT Press.

LaBelle, B., 2010a. Background Noise: Perspectives in Sound Art. New York: Continuum.

LaBelle, B., 2010b. Acoustic Territories: Sound Culture and Everyday Life. Kindle version. New York: Continuum.

Licht, A., 2007. Sound Art: Beyond Music, Between Categories. New York: Rizzoli.

Marx, K., 2004. Manuscritos econômico-filosóficos. São Paulo: Boitempo.

Massumi, B., 2002. Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation. Durham & London: Duke University.

Obici, G., 2008. Condições da Escuta: Mídias e Territórios Sonoros. Rio de Janeiro: 7Letras.

Oiticica, H., 1986. O q Faço é Música. São Paulo/Rio de Janeiro: Galeria SP/Projeto HO.

Oiticica, H. et al., 1996. Hélio Oiticica. Rotterdam/ Paris/ Rio de Janeiro: Witte de With/ Gal. Nat. du Jeu de Paume/Projeto HO.

Oiticica, H., 2010. Encontros. Rio de Janeiro: Azougue.

Oiticica, H., 2011a. Programa Ambiental. Doc. n.0253/66. In Museu é o Mundo, Rio de Janeiro: Automatica.

Oiticica, H., 2011b. Org.: Oiticica Filho, Cesar. Museu é o Mundo, Rio de Janeiro: Azougue.

Onfray, M., 2009. Teoria da Viagem: Poética da Geografia. Porto Alegre: L&PM.

Oliveros, P., 2004. Some Sound Observations. In: Cox, C.; Warner, D. ed. Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music. New York: Continuum.

Oliveros, P., 2005. Deep Listening: A Composer`s Sound Practice. Lincoln: iUniverse.

Ranciére, J., 2009. A Partilha do Sensível: Estética e Política. São Paulo: EXO Experimental/Editora 34.

Rainer, C; et al. ed., 2009. See This Sound: Promises in Sound and Vision. Cologne: Lentos Kunstmuseum Linz.

Rimbaud, A. 1993. Carta do Vidente. In: Lima, C. ed. Rimbaud no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: UERJ/Comunicarte.

Schaffer, M., 1997. A Afinação do Mundo. São Paulo: UNESP.

Schaffer, M., 2003. Open Ears. In: Michael Bull & Les Back, ed. The Auditory Culture Reader, New York: Berg.

Serres, M., 2001. Os Cinco Sentidos: Filosofia dos Corpos Misturados. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil.

Stewart, S., 2005. Remembering the Senses. In: Howes, D. ed. Empire of The Senses: The Sensual Culture Reader. Oxford/New York: Berg.

Thrift, N., 2006. Space. In: Theory, Culture & Society. London: SAGE Publications, vol. 23(2–3). Available from: http://tcs.sagepub.com.

Thrift, N., 2008. Non-Representational Theory: Space, Politics, Affect. New York/London: Routledge/Taylor & Francis.

Tiberghien, G.A., 2001. Nature, Art, Paysage. Arles: Actes Sud/ENSP.

Tiberghien, G.A., 2007. Finis Terrae: Imaginaires et Imaginations Cartografiques. Paris: Bayard.

Tiberghien, G.A., 2010. Bill Viola: Na Natureza das Coisas. Concinnitas, year 11, v. 2, n. 17, december 2010.

Tiberghien, G.A., 2012. Hodológico. Valise, Porto Alegre, v.2, n.3, y.3, July 2012.

Toop, D., 2010. Sinister Resonance: The Mediumship of the Listener. New York: Continuum.

Viola, B., 1988. Survey of a decade. Houston: Contemporary Art Museum.

Viola, B., 1995. Reasons for knocking at an empty house. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Warburg, A., 2009. In: Agamben, G. Dossiê Aby Warburg, Arte e Ensaios - Revista do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Artes Visuais – EBA/UFRJ,19.

Westerkamp, H. 2007. Soundwalking. Originally published in Sound Heritage, Volume III Number 4, Victoria B.C., 1974. Revised 2001. Published in: Autumn Leaves, Sound and the Environment in Artistic Practice, Ed. Angus Carlyle, Double Entendre, Paris, p. 49.

Bio

Leandra Lambert lives and works in Rio de Janeiro. Lambert works in the field of fine art and as an experimental composer and singer. She conducts sonic, visual, textual and performance experiments. She has made several presentations, and participated for CD and exhibitions. Currently she is focusing on contemporary art and issues on sound, hodology, fiction, and intersensoriality. She is a PhD candidate in Arts at the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ) and holds a Master in Fine Arts from the same institution. In 2012 she won first prize at the III Latin-American Electroacoustic and Electronic Composition Competition Gustavo-Becerra Schmidt in the category of electronic/experimental for the piece "Cortina de Ruínas" (Curtain of Ruins). In February of 2013 she had a Solo exhibition "Danças Atlânticas" (Atlantic Dances) at CCJF - Rio de Janeiro. The TechArtLab (TAL) currently represents her. www.leandralambert.com